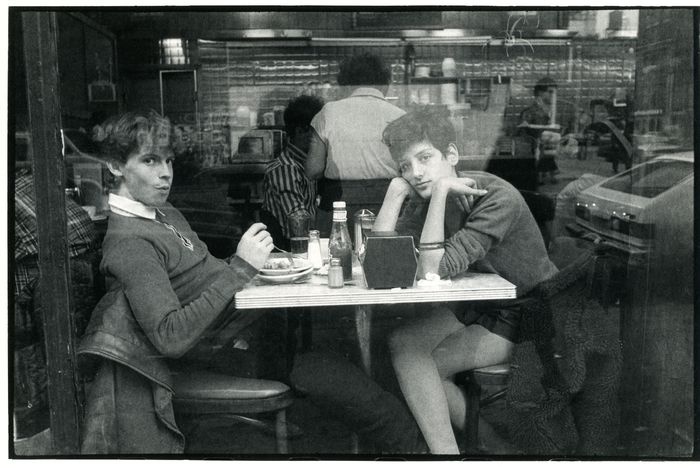

In keeping with family tradition, I was broke when I moved to New York in 2003. I wasn’t immigrant poor like my mother’s family was when they arrived in the 1900s, after escaping the czar, or like my father and his parents were when they landed a few decades later, after fleeing the Nazis. I had no money because I was 23 years old and all I wanted was to be a writer. I’d saved up a few thousand dollars for the move, and two hours after my bus pulled up at Port Authority, once I’d paid rent and other expenses, I was down to $500. That night, after blowing $50 of them at bars around Tompkins Square Park, I started to worry that I was going to be out on the street within a week. By 3 a.m., when my friends and I walked into a diner on Avenue A called Odessa, I wasn’t sure I should be spending any more, but then I looked at the menu and saw that I could order not only a plate of pierogi but also a side of latkes — which I’d been raised to believe could only be eaten during the eight nights of Hanukkah — for about $15. I knew I would walk out full and have leftovers for breakfast.

I spent those first few years working a mix of bad jobs at coffee shops, bakeries, bars, and restaurants, getting by on a wage of $6 an hour plus tips. I was prepared for certain New York struggles (noisy neighbors, bad dates). What I wasn’t prepared for was how when you’re broke, there are so many places in New York that don’t want you — a fact I felt most sharply when looking up and down the menus of nice restaurants. It wasn’t long after stumbling into Odessa that I realized there were other places like it: an entire enclave where I could eat my fill of the foods that bring me comfort without spending a lot of money. There was Streecha, on 7th Street, a spot in the basement of a brownstone where babushkas and punks sat next to one another eating sausage and cabbage. There was Ukrainian East Village Restaurant, a moody, stately place that I saved for special occasions and treated with a certain reverence, as if I were at a grandparent’s home. (When I walk in, I always feel the urge to take off my shoes.) There was Veselka, which, like Odessa, would have the lights on when I finished DJ-ing or bar-backing at five in the morning. There was B&H Dairy, a cramped kosher lunch counter founded with the Jewish neighbors in mind and serving more than a few recipes picked up as the Diaspora wandered throughout Eastern Europe. Once, when a roommate skipped out and left me to cover his rent and I had to figure out how to stretch my last $40 until I could ask my boss at the coffee shop for an advance, I spent two days bouncing between Veselka and B&H, surviving on borscht and coffee and refills of bread.

I use the past tense to make the point that there was a time when all of these places existed and I felt a sense of peace knowing that, at least in the case of Odessa or Veselka, I could wander in at any hour and order a familiar plate. When Odessa closed in July 2020, and Veselka stopped being open around the clock because of COVID, it was the first time in my adult life I didn’t know where to go if I woke up craving stuffed cabbage in the middle of the night.

Thankfully, Veselka is still there. So are Streecha and B&H and Ukrainian East Village. I have a little more money now, but my idea of a perfect day is the same as it was 20 years ago, when I would while away ten hours drifting from one Little Ukraine establishment to another, in search of a bowl of borscht, a plate of pierogi, and some stuffed cabbage. Then perhaps a shot of vodka to wash it down and maybe a cup of coffee and a cookie. And then maybe a few hours will go by and I’ll find myself wanting another meal, a tuna sandwich or a breaded chicken cutlet with kasha. And I can’t forget an extra side of beet-and-horseradish salad, which I try to always order ever since an old man sitting across from me in the sauna at the Russian & Turkish Baths turned to me unprompted and declared that all you need to live until 100 are beets, horseradish, a clove of garlic every single day, some cabbage, and a shot of vodka. “Fat, skinny, does not matter. You will live unless you die,” he stated before getting up and walking out, naked, into the small mass of people outside trying to enjoy the co-ed hours. If I have a little extra money to spend, maybe I will treat myself to dinner at Ukrainian East Village or a drink or two at Sly Fox, the perfect dark little bar next door. This is the only part of the city I know where you don’t have to live there but you can live there — at least until you’re ready to go home.

On a recent Saturday morning in March, I take the F train to Broadway-Lafayette, head toward Houston, and turn left on Second. When I show up at Veselka at 11, the line outside waiting to get a table is 25 people deep. Like every other restaurant, it has had a tough few years, but the customers have been returning, and when Putin invaded Ukraine, suddenly it seemed as though everybody in Manhattan descended. Third-generation owner Jason Birchard tells me that since the war started, his staff has made 2,500 gallons of borscht and too many pierogi to count. Veselka also makes its own version of the classic black-and-white cookie, iced in the yellow and blue of the Ukrainian flag. “Normally, I sell about a dozen a day,” Birchard tells me. “Now I’m making 300 a day. I can’t keep up.” I could probably ask Birchard to sneak me in, but I decide that would be gauche. Instead, I order a cherry-lime rickey, drink it outside, and go next door to Ukrainian East Village, where I find a table.

A group of six sits down next to me and orders. The way I hear one man at the table ask for borscht — a smoother variation on the word, with a little romance added to it — reminds me of my grandfather, who spoke an accented Yiddish, influenced by Ukrainians and Romanians, that I’ve heard referred to as Ukrainish. He was born in Chernivtsi, only he knew it as Czernowitz, when the city was still part of the then-crumbling Austro-Hungarian Empire. When he was a child, it became part of Romania and then, in 1940, was annexed by the Soviet Union, only to be occupied by the Germans and Romanians a year later, then made part of Ukraine after the Second World War. When I introduce myself to the man at the neighboring table, he confirms he’s from Chernivtsi, born a few decades after my grandfather, as a Ukrainian, not a Romanian. His group, he tells me, used to meet for lunch in Little Ukraine once a month or so; now, every week, they take the subway or drive in from Sheepshead Bay, Long Island, Connecticut. None of them has ever lived in the neighborhood, but it’s where they’ve always gone to eat because it feels the most like home.

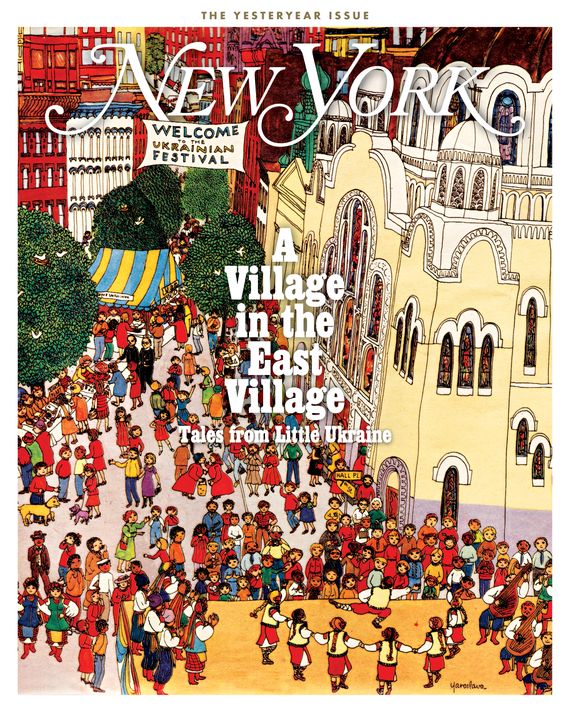

I ask for my usual: hot borscht and a can of ginger ale. In 1968, writing in this magazine as the Underground Gourmet, Milton Glaser and Jerome Snyder dubbed the western side of Tompkins Square Park between 7th and 10th Streets, where Odessa and Leshko’s were then located, the “Pirogi Belt.” The original Leshko’s closed in 1999, 20 years before Odessa did, so the Pirogi Belt is gone, but the Borscht River still flows a few blocks away: I suspect there is no place in America where as much borscht is made and consumed as on this little stretch of restaurants along Second Avenue. I have happily swum down this river many times. Thirteen years ago, I decided to sample all the Second Avenue borschts in one day, and I’ve repeated the experiment since, occasionally bringing friends who tap out after one or two bowls. By now, I can detect the most subtle differences among the street’s borscht offerings. I know, for instance, that B&H’s is more watery, ideal for soaking up with its challah, and comes with massive chunks of potatoes, making it the most filling version in the area. Streecha’s borscht has the most aromatic broth, its flavors more spiced than earthy; it comes in a cup, and it took me five years to realize that I could sip it while walking, like an order of coffee to go. Based on its color alone (light pink), I can distinguish Veselka’s cold summer borscht from its winter borscht with dumplings (crimson) and its chunky, all-seasons borscht (oxblood).

At Ukrainian East Village Restaurant, my borscht arrives, and on this particular Saturday, I decide that its version is all I need. It has an appealing viscosity, the broth sliding down your spoon slower than at other places. The vegetables are uniformly diced, and I would describe the fresh dill it’s topped with as “an NBA center’s handful.”

Before I pay the bill, I order a mixed plate of pierogi, eat one, and ask for the rest to go to bring home to my wife. Outside, I see that the line for Veselka is still wrapped around the corner, so I walk across the street to B&H and order the whitefish melt. B&H represents a classic example of New York City’s blurring of influences: Before it was Little Ukraine, Second Avenue was a destination for Jewish immigrants, and businesses like B&H were aimed at that clientele. Today, the boundaries between Ashkenazi Jewish food, New York diner food, and Eastern European food have grown less distinct. There’s a sense of balance I get around places like Streecha or Veselka, knowing that things like potato pancakes or borscht or blintzes weren’t the food of my people but that, eventually, my people learned how to cook them and they became part of the story, and now I’m part of that story too.

At B&H, I eat my melt, grab a coffee, then give up my seat to an NYU student who looks like he had a rough night that turned into a rough morning. I wander over to Streecha only to find it closed — the place, at least in my memory, has always kept odd hours. Many years ago, when I was 26, I brought a friend here. He ordered the kovbasa, or kielbasa, which came covered in caramelized onions, and I watched as he sliced into the sausage, the harsh hue of pink on the outside giving way to a lighter one inside. Soon after, he and I lost contact for no particular reason: The last I heard from him was a few years ago, when he was living out west trying to get clean and messaged me on Facebook to tell me he was thinking about that meal because he had recently had kielbasa and it didn’t size up.

People often talk about the joy of food, how a bite or smell can bring us comfort at the most tragic of times. There is never regret in ordering goulash or a bowl of borscht with a matzo ball, or in deciding you want the deluxe pierogi plate with the stuffed cabbage and kasha with mushroom gravy and a side of sour cream. There is only regret in the things you want to eat but don’t order and the things you want to say but never do. When I got the message from my friend, I told myself I would respond but didn’t, and a few months later, I found out he had died. Standing outside Streecha’s darkened windows, I find myself wishing I had told him how often I think about the look on his face when he ate that kovbasa.

The way I normally do Little Ukraine is to take it slow: Spend an hour or two at each place, go for a walk in between, and sit on a bench at St. Mark’s Church or stare at the theater where Stomp has, against all logic, been performed since the Giuliani era. And I always wind down the day with a drink at Sly Fox. The bar doesn’t open until six in the evening, and when I look at my watch, I realize it’s not even three. I wish I could say that I toughed it out: that I found a bench, read the book I packed but didn’t like, then walked into my favorite bar and ordered a shot of honey-pepper vodka, a Ukrainian specialty that feels more like a test than anything else. The vodka already burns going down, and the addition of chile pepper verges on cruel. (Once, at a party in Sheepshead Bay, I watched a Ukrainian Jewish man walk in right after a late-in-life circumcision and request a bottle of the Nemiroff honey-pepper vodka.) But on this specific Saturday, the sidewalks were just too crowded. As I head home, I reach into the bag of pierogi that I told my wife I’d save for her, pull one out, and eat it. Then another and another.

By the time I get back, I look in the bag and realize I’ve eaten all the pierogi. My wife seems disappointed, but she understands. Our early days were spent during the coldest months of the year in her apartment on 10th Street, ordering Veselka delivery, or at B&H when we wanted to go out and sit down. This food is part of who we are, both as people and as a union. There will always be more pierogi, I tell her. We can go to Little Ukraine and eat whenever we want.