Hiramasa is a small Upper East Side sushi restaurant in the 90s that sits across Madison Avenue from a J.McLaughlin store and an almost cartoonishly charming little bookshop that looks as if it exists in a fairy tale. Most nights, the six seats at Hiramasa’s upstairs counter are filled with neighbors and seafood lovers who have heard there’s something special happening at this under-the-radar sushi spot. On a recent, hushed Thursday evening, chef Jorge Dionicio was there, as he always is, carefully slicing and plating bites of Alaskan king crab, placed on a miniature stone garden and finished with a sauce of crab and miso — crab on crab, the miso’s sweetness complementing the crab’s. Then he placed uni and caviar atop crispy yuba. Dionicio’s seasonal omakase regularly features monkfish liver (ankimo), brown barracuda (kamasu), and blackthroat seaperch (nodoguro); one bite in particular that stands out is hamachi dressed with ponzu, serrano chilies, micro cilantro, and crisped potato, a surprisingly subtle combination that strays from traditional Japanese preparations and nods to the unique path Dionicio took to his big-city sushi counter — a road that includes stops in Nebraska, Texas, and Tokyo and began in Dionicio’s native Peru.

“I could show off more if I was cooking Peruvian food,” the chef explains. “But I’m about respecting the tradition — I try to not be crazy with too many sauces.”

The approach and his appreciation for customs have helped Dionicio build a small but dedicated following in the seven months since Hiramasa opened. The prices have helped, too: Dionicio typically charges $125 for a ten-piece tasting menu, which is not cheap, but within the rarefied world of high-roller Manhattan sushi, the price — and even the $225 he charges for a 20-to-24 “grand omakase” on weekends — is a relative bargain. As the cost of ingredients skyrockets, so has the barrier for entry at various luxury-seafood counters around town. At Noz and its new offshoot, Noz 17, a meal at the counter begins at $400. That’s roughly in line with what you’ll pay at 69 Leonard in Tribeca and Icca near City Hall. Dionicio is fastidious about managing costs and stretching ingredients, skills he says he picked up while working as a supervisor at a Cheesecake Factory in the early aughts: “That’s when I saw everything and really understood how a restaurant runs.”

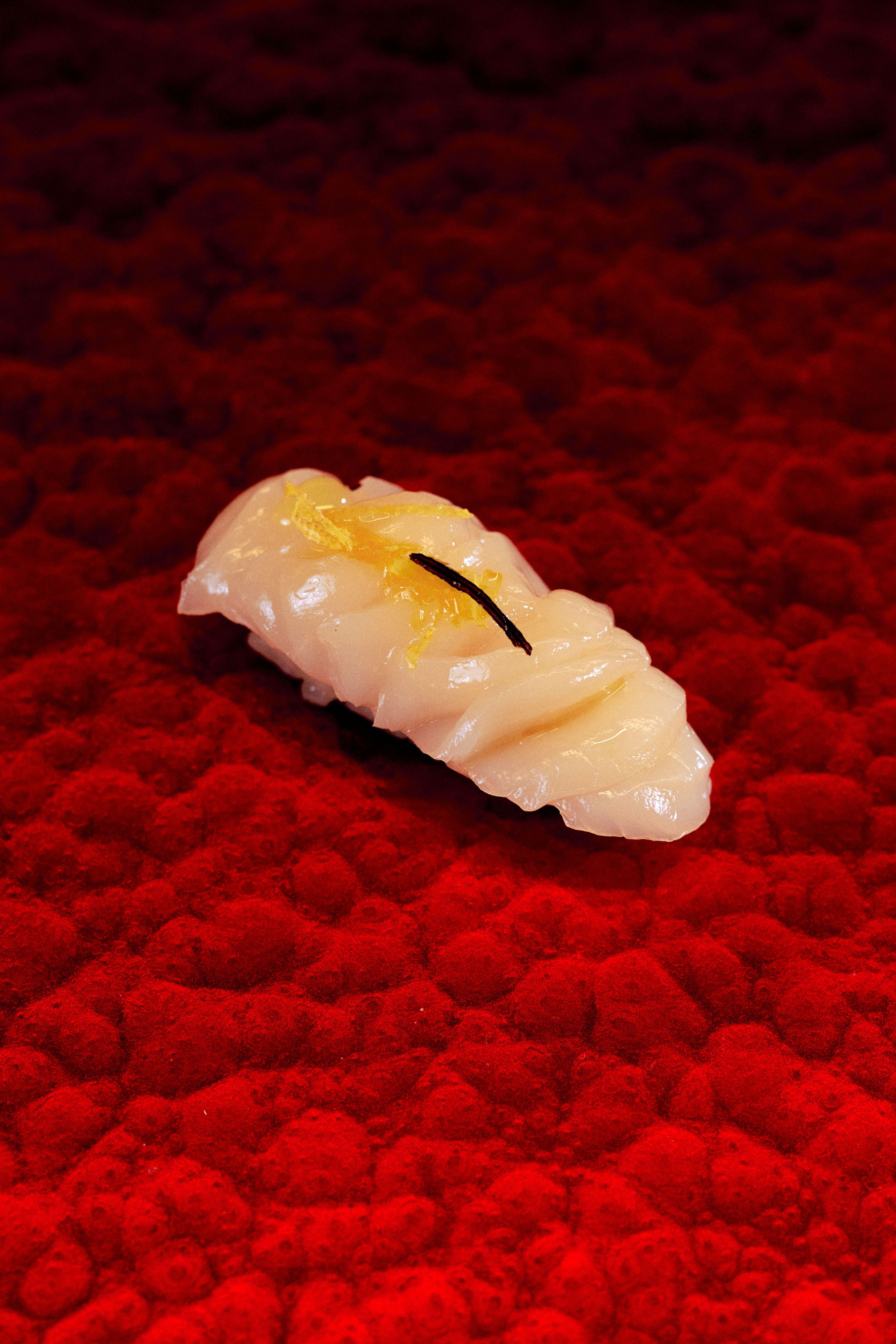

Hokkaido scallop.

Almost all of Dionicio’s seafood — with the exception of oysters and king salmon — comes from Japan’s Tsukiji market.

A Kumamoto oyster.

Chef Jorge Dionicio at Hiramasa, which opened last fall.

Zensai: hotaru ika (firefly squid), Hokkaido uni (sea urchin), and awabi (Japanese abalone).

Kanpachi tiradito.

Hokkaido scallop.

Almost all of Dionicio’s seafood — with the exception of oysters and king salmon — comes from Japan’s Tsukiji market.

A Kumamoto oyster.

Chef Jorge Dionicio at Hiramasa, which opened last fall.

Zensai: hotaru ika (firefly squid), Hokkaido uni (sea urchin), and awabi (Japanese abalone).

Kanpachi tiradito.

Dionicio was born in Peru then moved to Omaha, which was not exactly how he’d imagined the United States. “The airport was smaller than the one in Lima,” Dionicio laughs. “It was a big shock.” As a teenager in Omaha, he got a dishwashing job at P.F. Chang’s before moving to an Asian-fusion restaurant — this was the early aughts, remember — with a sushi counter. At first, the restaurant did not seem like the best place to launch a career as a serious sushi chef, and not only because it was in a landlocked state with less than 1 percent of its total area is covered by water. “Everyone who worked there either got fired or quit,” Dionicio recalls. To take him in as a sushi chef in training, “the Japanese chef said to me he had to cut my pay from $14 an hour to $7 an hour.” Dionicio didn’t see the position as a demotion because he was determined to learn. “Money was always secondary,” he says.

The restaurant had a reverse happy hour from 10 p.m. to midnight, when crab and spicy tuna rolls were served. Dionicio perfected the rolls during the graveyard shift: “I was always thinking how I could make them better.” He worked six straight weeks, 15 hours per day, with no tips. He persevered and impressed his boss, but he knew he couldn’t stay in Nebraska forever.

Eventually, he spent a year working in Tokyo, where he completed training at the World Sushi Skill Institute, at one point placing seventh in Tokyo’s World Sushi Cup. Dionicio says it was in Japan where he began to fully understand the intricacies of top-tier sushi-making: “I can cut hamachi in three different ways, and each type of cut gives the fish a different taste.” Before the pandemic, Dionicio spent at least one month a year in Japan, though he eventually made his way back to the States, working at O Ya, the onetime sushi hot spot in the Flatiron District, and in Dallas.

He relays the story to me over dinner at Mission Ceviche, the Upper East Side restaurant that got its start as a fast-casual lunch counter in the Meatpacking District, another unlikely origin tale for a restaurant that, according to Dionicio, offers some of the best seafood in the city. “This ceviche,” he says between bites of lightly cured mahimahi, “is very close to what we have in Peru.” I ask why that is. “The fish is fresh,” Dionicio explains. “It’s very easy to tell if it’s been previously frozen.”

Most of Dionicio’s fish at Hiramasa flies in from Japan’s Tsukiji market each week, and on delivery days, he starts the morning by breaking everything down, employing the Japanese principle of mottainai, which, loosely translated, means “Use everything you can and have no waste.” Then it’s on to making rice and tamago and prepping the menus for each night’s omakase. Service lasts until 11 p.m., when the last guests have left. That’s when Dionicio starts to close and clean the restaurant. Around midnight, he says, is when he begins to think about the next day’s menu and placing his orders from Japan.

Most weekdays, he’s home at his apartment, located close to the restaurant, by 2 a.m. Even by the standards of a chef in New York City, it’s a very long day. Like many restaurants, Hiramasa is facing a tough labor market. The restaurant has around 16 staffers but no general manager, so Dionicio is temporarily working both the front and the back of the house. Even still, it’s a long way from the sushi-counter graveyard shift in Omaha, where he made the same rotation of happy-hour rolls. Though he took that job seriously, he knew it was only the beginning. “I cried many times,” he concedes, “but I knew I just had to keep going.”