The name Shorty Tang still looms large in the history of Chinese cooking in New York City. New York had already taken to calling the chef “legendary” in 1973. At the height of his fame, his restaurant — Hwa Yuan, which opened in 1968 — sold a quarter-ton of noodles each day. Cold sesame noodles, the type available at every takeout joint in New York, largely exist because of Tang’s original (superior) recipe. That restaurant, and the many others it inspired, have long since closed, but now Tang’s son and grandson are set to carry on Shorty’s legacy with two new restaurants: a new, palatial Hwa Yuan in the same spot as the original, and a smaller noodle shop named for Shorty himself.

Sam Sifton revived Shorty’s legend in 2007 with a column about the chef: “His sesame noodles were soft and luxurious, bathed in an emulsified mixture of sesame paste and peanut butter, rendered vivid and fiery by chili oil and sweetened by sugar, cut by vinegar, made fantastic by technique,” Sifton wrote at the time. One problem, as Sifton points out, is that the original recipe has been lost and bastardized over time to the point where the city’s current sesame-noodle offerings are pale imitations of the storied original.

It is one of Tang’s six children, Chen Lieh Tang, who will resurrect that original recipe. “I still make my own,” says the spry 62-year-old restaurateur. “I don’t let other people touch, because it’s very difficult to make.” He says some recipes have gotten close, but genuine specs demand that the egg noodles be made with icy water. There’s also the inclusion of homemade Sichuan cabbage, and, in a surprising twist, Chen Lieh says a bit of collagen-rich chicken soup also figures in.

Yet the dish’s origins still bear a trace of mystery. “Where do you even get peanut butter? It’s such a non-Chinese thing,” says James Tang, Chen Lieh’s son. James, 32, works in finance but will be managing partner at both restaurants. “Maybe it was an army-rations thing.”

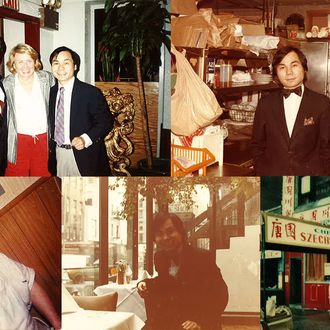

Shorty — not his given name, but one suited to fit his stature — began his apprenticeship in Sichuan food at 12 and never stopped cooking. “He came in on his day off to check every detail and delivery because he wanted to make sure no one would complain,” Chen Lieh says. Shorty died in 1976, at age 50, but he taught Chen Lieh the recipes: Classic shrimp with white sauce was first. Carp with hot bean sauce looked easy enough to replicate, but was in fact one of those deceptively difficult dishes to reproduce. Chen Lieh learned how to be nimble with chiles, when to add the snap of scallions and young ginger, to balance flavors with the tannic depths of rice wine. There were tricks to greaseless scallion pancakes and ultralight pork meatballs. By the mid-’70s, Hwa Yuan managed to stand out among the city’s enormous roster of Chinese restaurants. Mobsters devoured double-sautéed pork. Future mayors — Giuliani, Bloomberg, Koch — stopped in. Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw could be found there on dates.

By the time Mimi Sheraton awarded Hwa Yuan two stars in 1982, Chen Lieh had moved on to open Tang’s Chariot in midtown, where Gourmet magazine praised the “first-rate” sesame noodles in a full-page review. A dozen places with names like Tang Tang, Tang Tang II, Tang Tang Noodles, and Tang’s of Westport followed.

But Chen Lieh swore off the industry altogether nine years ago, after the financial crisis hit. He spent part of his retirement in Taiwan. “[But] I had to go back to work,” he says now. Bouncing around the dust-filled, unfinished Chelsea dining room that will soon reopen as Shorty Tang Noodles, it’s Chen Lieh himself who oversees every single detail: servers’ uniforms, door knockers, chopstick holders, the wallpaper, even the pitch of a skinny floor drain in the kitchen.

When it opens this fall, Shorty Tang Noodles will have six tables and a bar where diners will be able to look directly into the kitchen. In addition to its namesake option, the menu will include steamed rice rolls with pork or beef, and a style of beef noodle soup that’s synonymous with the family name in Taiwan.

The new Hwa Yuan, however, will be a far more grandiose affair: Standing on the exact site of the original — currently Bank of China on East Broadway, which the Tang family owns — Hwa Yuan was, and will be, a vast, three-floor restaurant. The Tangs are aiming to get it open by the end of the year, and when they do, the space will be magnificent: Slabs of translucent tortoiseshell marble, private rooms, and an opulent, Tang-designed golden centerpiece called “The Mushroom” all figure in.

There will be a stand-alone raw bar, and customers will see cooks preparing Peking duck, part of which takes place in a large bull-nosed oven from Hong Kong that Tang calls the “bullet train.” The menu will run to 50 items, with new dishes joining classics like Marvelous Orange Beef, an updated version of Shorty’s famed carp and hot bean sauce, and, possibly, a version of Beggar’s Chicken that will be stuffed with cabbage, ham, and shrimp — a whole bird with the same showstopping magnitude as Mission Chinese Food’s massive postmodern roast chicken.

“The first thing we thought about was getting a new bank to take the space,” James says. “They’re the best tenants.” “[But] everybody was saying, ‘You need to open a restaurant.’” Indeed, if Chen Lieh Tang was at all reluctant to dive back into the restaurant world, it was his former neighbors who helped push him over the edge. The idea, he says, is to open a place that stands a chance of lasting 100 years in New York City. “I want to bring back Chinatown,” Chen Lieh explains. Even members of his former kitchen staff, long since dispersed to start their own restaurant empires, are returning to help restore Hwa Yuan’s former glory. “I called them,” Chen Lieh says. “They all will return.”