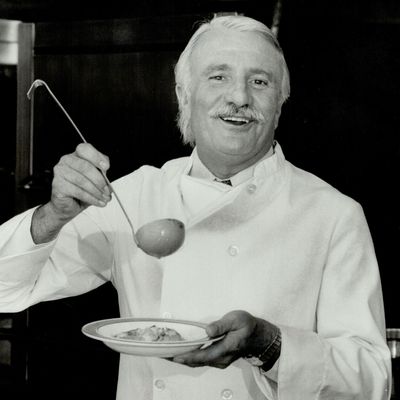

Roger Vergé — an influential chef and restaurateur who famously shunned the spotlight, but who nonetheless was instrumental in creating the modern era of celebrity chefs — died at home in Mougins, France, on June 5. He was 85.

The chef was born April 7, 1930 in Commentry, France. Like several of his contemporaries, Roger Vergé came from a working-class family. He credited his aunt, Célestine, to whom he later dedicated a series of cookbooks, as the person who introduced him to cooking, and at the age of 17, Vergé eschewed what would no doubt have been a surefire (and more lucrative) career path as a pilot in favor of taking a low-level kitchen job at a restaurant in his hometown.

Grueling apprenticeships in Paris’s toniest brigade-style kitchens at the Tour d’Argent and Plaza Athénée followed. Vergé then cooked in North Africa before moving to Kenya in 1955 to work for the food-service division of an airline. It was during this time that the chef began to reconsider his approach to ingredients, and pull apart the through-lines of butter and cream that were the dominant hallmarks of textbook-modern French food. While he never exiled beurre blancs from his restaurants completely, Vergé devised menus to include a broader palette of Provençal and Mediterranean flavors, many of which had been dismissed previously for being too regional or low class to fit in with refined standards like pastry-wrapped terrines and the high-maintenance workhorse dishes of the Escoffier era. In doing so, Vergé became a de facto champion of using locally sourced ingredients over what was then a kind of rote faithfulness to the old-school approach practiced by his peers who polished their skills in culinary academies.

Vergé was a proponent of fruits, for example, that had long been relegated to the pastry department. Most often, oranges were cooked down in molten sugar and apples were stewed beyond recognition; now fanned, raw slices alongside rare Magret duck, and tiny orange supremes were served nestled with just-cooked-through oysters broiled on the half-shell with a dab of orange butter. The latter dish wowed New York Times critic Craig Claiborne. “Before I lived in Africa,” Vergé told Claiborne in 1981, ”it had never occurred to me to combine the flavors and textures of fruits with savory foods.”

What seems more like a culinary given these days was deft and revolutionary in the 1970s, in Michelin star-besotted France. Vergé opened the restaurant Moulin de Mougins with his wife, Denise, in 1969. He added brightness to dishes with olive-oil-preserved lemons and fatty mouthfeel with raw avocado. Rather than relying on the wheelhouse of slurries and rouxs, Vergé ratcheted flavors with layered stocks and added dimension with vinaigrettes. He soon had three Michelin stars and opened a second restaurant in 1977. His Barigoule-style artichokes were famous. Vergé’s savory gâteaus bound with clarified and reduced stocks were imitated by dozens of chefs. Along with chefs such as Paul Bocuse and Michel Guérard, he became known as a proponent of nouvelle cuisine. Vergé branded his own style Cuisine du Soleil, or “Cuisine of the Sun.”

A chance meeting with Shep Gordon in 1972, when the famed talent manager was in town for the Cannes Film Festival, led to an unlikely alliance. Gordon was drawn to Vergé and even became his apprentice for a time; the pair traveled the world and gave cooking demonstrations, putting the chef on par with bona-fide rock stars like Alice Cooper, whom the agent also represented. This was unheard of, Gordon later recounted, because “nobody respected the culinary arts.” Shep Gordon went on to be instrumental in launching the careers of celebrity chefs such as Emeril Lagasse and Daniel Boulud.

The long list of future titans of fine dining who spent time working for Vergé include Alain Ducasse, David Bouley, and Jacques Maximin. Daniel Boulud himself cooked for Vergé at Moulin de Mougins, and recounted for this month’s Haute Living how Vergé, his “biggest influence,” sent him to further his education in Luxembourg and then to Denmark, where the elder chef paid for Boulud’s Berlitz course in English. In his appreciation, Boulud called Roger Vergé “the ‘Cary Grant’ of the culinary world.”

Roger Vergé never quite sought to establish the global empire established by the Ramsays and the Robuchons of the world, but he still wrote cookbooks, opened a cooking school, and sold olive oil and wine. He opened two properties at Epcot Center with Paul Bocuse and famed pastry chef Gaston Lenôtre in the 1980s, but never had the kind of marquee-name success enjoyed by Bocuse. (The trade publication Food Arts characterized Vergé as the “Sundance Kid to Paul Bocuse’s Butch Cassidy.”) He eventually opened an ill-fated restaurant in Rockefeller Center called Medi, which opened a month prior to September 11, 2001, and served a $38.50 gold-tinged Scotch egg. Vergé left his role as consultant after eleven months.

Vergé was often at his best when his cooking was its simplest. His three-ingredient recipe for fried eggs with vinegar kicks off Food 52’s excellent Genius Recipes book and is a masterclass in elegance. Along with Michel Guérard’s confit byaldi, the chef’s tian of tomatoes and zucchini informed the inspiration for the pivotal presentation of ratatouille in the Pixar movie of the same name.

Roger Vergé retired in 2003, but remains an influence, even for chefs who may not be aware of his name. Much of this has to do with the fact that he preferred his kitchens and dining rooms the most. “What I learned from Mr. Vergé,” Shep Gordon said his namesake documentary released last year, “is that you can be successful and happy. I had only seen success and misery. And his joy came from always putting the comfort of other people before his own.”