When Marco Canora opened Brodo, the broth-focused kiosk attached to his East Village restaurant Hearth, he was mostly just looking for a way to make a quick buck. In New York’s crowded, costly restaurant world, even a revered chef like Canora has to continuously hustle — especially since his rent at Hearth was hiked 65 percent last year. He needed more money, quick. “Necessity is the mother of invention,” he says, adding that he figured he’d wind up making a few extra hundred dollars a day, max. Instead, while declining to offer specifics, he says he’s making “a lot more than that,” and his tiny takeout window has launched one of the country’s fastest-burning culinary trends, a surprising feat for one of the world’s most ancient and basic foods. “Everybody saw what that window garnered,” Canora says. “There’s no barrier to entry.” Of course, Canora probably also wasn’t anticipating a backlash that seems to have arrived just as swiftly.

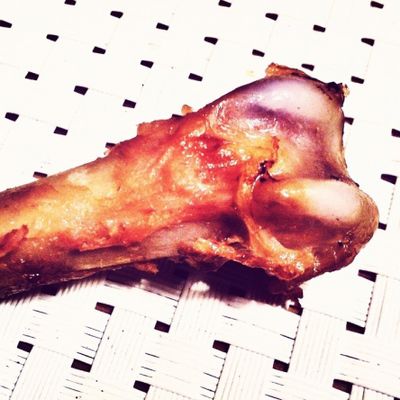

At Brodo, Canora makes his broth by boiling bones, meat, and seasonings together for hours on end. The kiosk offers three styles of broth: gingered beef, chicken, and the signature Hearth Broth, which serves as the base for many of his restaurant’s dishes and is made from turkey, beef shin, and stewing hens. Since that East Village takeout window opened last fall, bone broth outlets have cropped up or gained steam in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Austin, and Portland, Oregon, where a new broth bar is scheduled to open this summer. There are also delivery services, like the San Diego-based Bare Bones, which ships nationally. And in perhaps the biggest development, Panera pounced on the trend and began offering “Asian-inspired broth bowls” just a few months after Brodo launched. While other health-focused foods like kale and quinoa took years to creep into the national consciousness, bone broth’s rise was more or less immediate.

Social media obviously helped spread the word about the rise of broth, and its subsequent explosion in popularity makes sense for several notable reasons: It’s cheap and easy for chefs to replicate, it already had a foothold in Paleo-diet circles, it tastes good, and perhaps most important, it seems healthy-ish.

In 2009, the Paleo food blog Nourished Kitchen extolled the purported virtues of bone broth. In 2013, Pacific Foods soon began selling “bone broth” in grocery stores, using the term to differentiate the product from other additive-heavy, meat-light packaged broths that were already on the market. And it’s the Paleo crowd that has largely been arguing that bone broth is something of a miracle cure-all that can calm your gut, clear your acne, and mostly just make you feel like a rock star. Advocates say this is because the high cooking temperatures and long cooking times help leech minerals and vitamins from the nutrient-rich bones into the broth.

Of course any meteoric rise is also bound to bring out critics, and the broth backlash seems uniquely angry and pronounced. Detractors cry foul over any supposed health benefits, and say the bone broth fad is nothing more than a way for chefs to sell gussied-up soup stock for a few dollars more. (It also didn’t take long before people compared broth to Arrested Development’s notorious “hot ham water.”)

Many of Canora’s culinary critics are less worried about health benefits than whether there is anything new about the current generation of bone broth — or whether it’s just a marketing sleight of hand, a way to sell a product that’s identical to stock that’s being made in less-fancy kitchens around the city. In fact, prominent food writer Kenji López-Alt recently took some very public umbrage, disputing the idea that any new ground has been broken at all:

“The way bone broth is sold to people is you take bones and boil them for a long time, and the implication they’re making is that people weren’t doing this before,” López-Alt argues. “It’s intentionally misleading customers into thinking they’re getting something very special.” He adds that his complaint isn’t just about consumer advocacy, it’s also about shining a light on other places that make something similar. “It diminishes what other people have been doing, like the Vietnamese place that has been boiling broth for three days for their pho and is charging much less for the whole package — because they’re not marketing it this way, they’re not cashing in.”

Canora doesn’t agree: “You want to name things that sound appealing, that draw attention,” he says. “When cold-pressed juice came out, I didn’t hear a bunch of uproar about how these guys are just creating a term to charge more money.” He also points to another explosively popular food: “Nobody talks shit about naming something the Cronut.”

Even still, Canora seems less worried about criticisms and more focused on figuring out how to handle another more immediate threat to the demand for bone broth: summer. Stretches where the thermometer regularly hits 80-plus degrees don’t exactly put people in the mood for steaming cups of bone-fortified liquid, no matter what you call it. So Canora says he’s trying to come up with a way to make something like an “iced-coffee version” of broth (possibly freezing broth cubes and using them to chill something like iced tea), but he’s also considering the possibility of just shutting Brodo down until the weather cools off again. In that case, he says people will be more than welcome to criticize bone broth once more: “I don’t care. It’s a free world,” the chef says. “If some people want to say I’m raping and pillaging and selling meat-flavored water, that’s fine.”