At Taqueria Ramírez, a small Greenpoint taco shop where you’ll regularly find a line of hungry customers stretching out the door, the lard has been bubbling since August. That’s when the shop opened, and in that time, nearly every taco it has served has been anointed with at least some of the manteca madre — “mother lard” that chef and co-owner Giovanni Cervantes originally procured from Casablanca Meat Market in East Harlem. Every day, the lard is loosened with an equal amount of water, which is then fully evaporated before the process begins again the next day. Rendered and re-rendered in the shop’s choricera, the manteca becomes deeper and better, fortified with the essence of every cut of meat that is simmered within this everlasting lard.

The pool of porcine splendor — which lends its complexity to Ramírez’s tripa, suadero, and even nopales — is hardly a secret. It sits just behind the counter; the phrase “All may contain lard” is scrawled in red, below the menu, on the tile wall beside the register. “When we decided to put it on the wall, it was a way of not being super-PC,” Cervantes says. “It was more like, Boom, this is how we do it.”

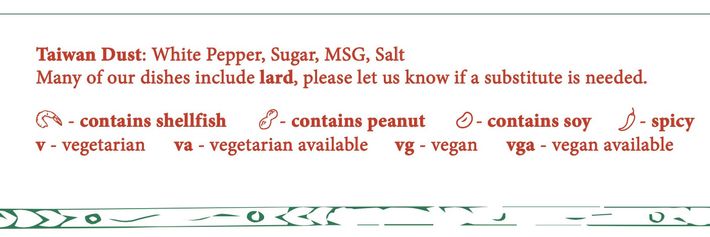

One fan of the proclamation is Eric Sze, the chef and owner of the Taiwanese restaurant Wenwen, which recently opened nearby: “I loved Taqueria Ramírez when I went, so the fact that they have the line,” he says, “you’re putting your — for lack of a better term — genitals on the table, and showing everybody what you got, take it or leave it.” When Wenwen opened earlier this month, its menu contained a similar, neatly typed note: “Many of our dishes include lard.”

“This is us,” declares Sze, “and if you don’t like it, then go to Bonnie’s.”

Justin Lee, the owner and chef of Fat Choy, includes the tagline “Kind of Chinese, also vegan” on his own restaurant’s menu, and he sees the value in such declarations — even if his is essentially the opposite of an ode to lard. “It’s less divisive, but we’re also doing something we believe in,” he explains. “It’s really not that different from them saying, We’re going to use lard.”

Lard, of course, has deep cultural significance in both the Mexican and Taiwanese culinary traditions: Cervantes speaks of the “intrinsic” link between pig fat and masa, while Sze compares lard to Chinese butter, scooped from tubs into stir-fries, heated up to frizzle shallots, and sandwiched between dough, as in the flaky scallion pancakes and sesame-crusted shaobing I grew up eating in Taipei, the moisture in the lard evaporating and exploding the laminated pastry into cottony layers. “Lard is awesome,” Sze says. “It works like butter, except it doesn’t overwhelm your palate.”

Yet even with that history, lard remains divisive, and not only to the people who avoid pork on religious or ethical grounds. At Taquiera Ramírez and Wenwen, the menu notifications read like a definitive rejection of the plant-based clean-eating wellness-babble that has managed to saturate American food marketing over the past few years — even if lard never really went away.

You might have had it this morning in sausage, sfogliatelle, or refried beans. It’s molded into the shape of a cartoon pig at Francie and pan-fried into the truffle mash at St. Anselm. But somehow, the idea of lard remains associated with cheap, grease-trap cooking that will leave yellow clumps on your artery walls — even though the reality is that it’s an inexpensive, versatile fat with a relatively high smoke point and rich, aromatic flavor, an ingredient that also happens to contain less saturated fat than almighty butter.

When it’s derived sustainably — not as a by-product of industrial farming but from pigs that eat grass and roam under the sun — lard can even be part of a healthy lifestyle, according to Kimberly Plafke, production manager at the Meat Hook. “There’s this huge stereotype that’s been ingrained in my generation that if you’re eating pork fat in place of margarine, you’re going to be overweight and unhealthy and have bad skin,” says Plafke, who goes by Steak Gyllenhaal on Instagram. “But I eat pork fat every day and I feel great all the time. I have other problems, but they have nothing to do with pork fat.”

The author Bill Buford calls lard “an expression of utter deliciousness and possibility” with an “ancient, ancient tradition.” When he phoned me during a family ski holiday to answer my questions about rendered pig fat, he added, “There’s something very beautiful and old-fashioned about using lard — it’s part of a traditional kitchen’s equipment.” Meanwhile, Aaron Foster, who renders lard from whole Pennsylvania pasture pigs at his market Foster Sundry, says it is “something that went away with our grandparents, like knitting and sourdough baking, that has come back into fashion. There’s something outré about it,” he adds, “because our parents wouldn’t be caught dead touching lard, and there’s something nostalgic about it.”

Sze, however, thinks the ingredient was demonized not for health or environmental issues, but because of cultural bias, an attitude he hopes his menu might be able to change. “It’s like the MSG thing,” he says. “We’re not ashamed of using MSG, we’ve done the research and know that it’s good, so it’s up to the diners whether or not they want to fuck with it.” And what has he discovered in the weeks that Wenwen has been open so far? “Overwhelmingly, people do want to fuck with it.”