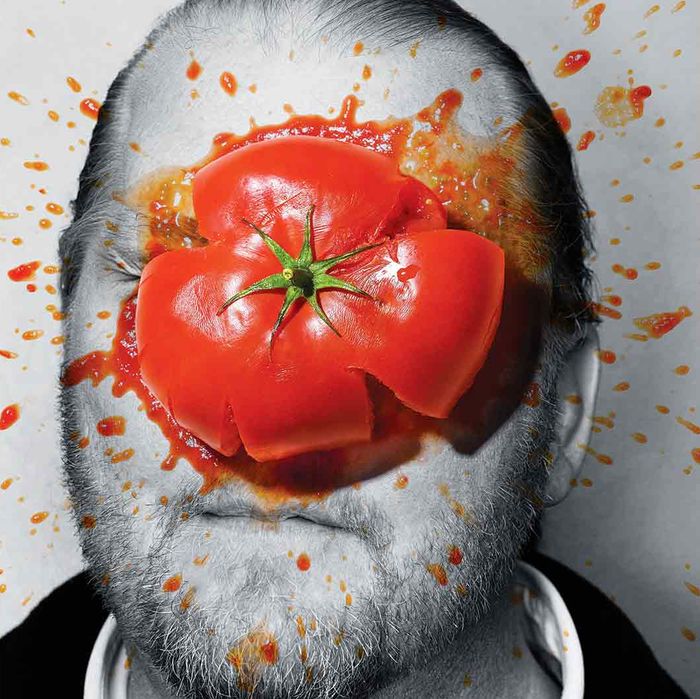

When the allegations of Mario Batali’s sexual misconduct came to light last December, the fallout was immediate. By the time the first story was published on the website Eater — including accusations that ranged from unwanted propositions and forcible touching to the kissing and groping, caught on security videotape, of a woman who appeared to be unconscious — the celebrity chef had agreed to remove himself from the operations of his two dozen–plus restaurants.

Then, in May, the New York Times found that the New York Police Department had launched an investigation into a claim from a woman who said Batali had drugged and raped her in 2004 at Babbo, one of his restaurants. The same month, 60 Minutes interviewed a woman who said Batali had sexually assaulted her in 2005 while she was passed out in a VIP room at the Spotted Pig, a restaurant where he is not a chef but an investor. The third-story space was apparently known to employees and people in the industry as the “rape room.” In August, the Times reported that the New York State Attorney General’s office had issued a subpoena for records related to Batali and the restaurant’s owner, Ken Friedman, including video footage of Batali with female employees in the room.

For Joe Bastianich, the business partner with whom Batali had founded and built their restaurant empire over the course of 20 years, the full effect of Batali’s transgressions was only beginning. “On the day in December that it broke, I had to walk into these restaurants and talk about these allegations,” Bastianich said. Their properties included Esca, Del Posto, Lupa, and Otto in New York, along with outposts nationwide and abroad. “To see people who were crying — I became emotional at some of these meetings,” Bastianich added. “It was real. Some of them felt angry. Some felt betrayed by Mario. To me, it was about bringing a bit of spirituality to the situation and immediately moving to create a new corporate culture.”

Bastianich was speaking over lunch at Babbo. He wore drawstring pants, a Grateful Dead T-shirt, and a black baseball cap. He was accompanied by the “crisis PR” representative Adam Goldberg, a lawyer from Washington, D.C.

Bastianich agreed to be interviewed but stated that he would not discuss his relationship with Batali prior to the first reports of misconduct. He was proud to state that among the first measures he informed employees about was a decision to ban Batali from setting foot in any of their restaurants again.

For some in the restaurant world, even that wasn’t banishment enough. Anthony Bourdain, the late chef, author, and TV star and Batali’s onetime co-traveler on the food-promotion circuit, argued that the only conceivable path forward for Batali was to disappear permanently. “Go off to an island, get yourself a hammock, and, you know, read,” he declared on the podcast Carbface, co-hosted by his assistant, Laurie Woolever, who once worked for Batali.

But even if Batali had found an island to retire to, there was still the entire cottage industry built around him to consider: cookbooks, retail food products, TV shows, and Eataly America, the emporium franchise. It was an open question if his business could survive without him or whether the public’s associations with him would sink the brand. A few days after the initial revelations, Bastianich visited Batali at his apartment just north of Washington Square Park. “I wasn’t there to incriminate him,” he said. “I was a wreck. It was already apparent to him that he was going to have to be out of this agreement permanently. We were there like five minutes. All of our history together at that point didn’t seem to mean anything. I was focused on what was going to happen to 30 restaurants.”

As everyone quickly moved to cut their ties and erase Batali’s name and likeness, Bastianich watched business drop in their restaurants by as much as 30 percent. In July, the Sands Casino ejected five B&B Hospitality Group restaurants from their properties, three in Las Vegas and two in Singapore.

“I’m dealing with a lot of negativity, these closings, to go tell 300 people we’re doing away with their jobs and shutting down their workplace,” he said. “We used to have 2,000 employees, and now we have 1,500. That’s how many families whose well-being we can no longer provide.” He talked about the new programs now in place for his staff to report misconduct and harassment, as well as how moved he has been by employees’ determination to keep kitchens and dining rooms running.

Friends and colleagues say it particularly angers Bastianich that, almost a year after Batali was publicly dropped from the partnership, negotiations to buy him out remain unresolved. Anybody who eats at Babbo nowadays, in other words, is still paying Batali.

But Bastianich has been firm in stating that he never personally saw Batali do anything untoward. “Drinking a lot is not against the law, the last time I checked,” Bastianich said. “I’m saying what I said in the statement at the time: The allegations were shocking. There’s some touchy stuff here. I thought about the allegations. We made some statements, and it’s all been documented already.”

At such pains to distance himself from Batali, Bastianich affected ignorance about basic details, including where the attacks allegedly took place. “I’m still an investor in the Spotted Pig, but I’ve never had anything to do with it,” he said. “Did one of these happen in our restaurants?”

His PR man quickly cut in to address the claim from the woman who said Batali had raped her at Babbo. “She didn’t come forward to us,” he said. “The NYPD never contacted anybody from the company.”

Bastianich went back to his script. “The newer allegations were even more horrific in nature,” he said. “How was I supposed to feel? I felt terrible.”

While Bastianich struggles to navigate a way forward for the hospitality brand he and Batali built together — amid questions about whether it should even have one — Batali’s downfall has caused something of a reckoning within the food world. Did everyone around him simply turn a blind eye to his conduct, or did they in some way enable it? And would getting rid of Batali make enough of a difference on its own? The full extent of what his victims endured is still being processed by the criminal-justice system, but the horror that has already emerged is palpable from their descriptions. On 60 Minutes, an anonymous former employee at Babbo recounted drinking white wine with Batali one night at the Spotted Pig after he’d invited her to a party there. She noticed she felt “completely foggy,” and then, she said, “it all disappears.” She woke up at dawn in an empty room in the building, surrounded by broken bottles. She had what looked like semen on her leg. When she went to work and asked Batali what had happened, “he was just silent, wouldn’t talk to me.”

In his initial apologies, Batali “vehemently” insisted that any sexual activity he engaged in had been consensual, and he appeared to think that a bit of his good-natured and freewheeling hospitality could earn forgiveness. He began his emailed newsletter by taking “full responsibility” for his “many mistakes” but closed with this: “P.S. In case you’re searching for a holiday-inspired breakfast, these Pizza Dough Cinnamon Rolls are a fan favorite.” In a statement to Eater, he wrote, “We built these restaurants so that our guests could have fun and indulge, but I took that too far in my own behavior.”

It’s true that Batali reveled in excess and was celebrated for it. It wasn’t uncommon for him to go through an entire case of wine over the course of a day. He once wrote an essay for The New Yorker’s website about his friendship with the late novelist Jim Harrison, a known gourmand, about “that night we ate just about every non-grocery-store cut of every animal I served,” a 15-course meal washed down with two magnums of vintage Barolo, “then a double mag of Le Pergole Torte, then back to the north for some Gaja Barbaresco with which we ate a couple of robiolas and a mountain Gorgonzola with housemade black-truffle honey.” Describing this relationship in his book Heat, about his apprenticeship at Babbo, Bill Buford writes that the two men “could have been walk-on parts in a medieval play about the deadly sins (all seven).”

In 1999, when Batali suffered an aneurysm on Lupa’s opening night and had to be taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital, employees expected the episode would force him to slow down, but it seemed to have the opposite effect. Babbo sometimes stayed open until 2 a.m. as Batali held court on the front stoop, smoking cigarettes and drinking Averna from an espresso cup. Then it was on to the Spotted Pig until daylight. His restaurants’ devotees included Bill Clinton, Michael Stipe, Bono, Jay-Z, Jimmy Fallon (a Friday golf partner), and Jake and Maggie Gyllenhaal. “He was a voracious consumer — not just of food and wine but of people,” says a food-magazine editor, “even though there was obviously something unseemly about the way he went after celebrity friends and women who weren’t his wife.” (Batali is married to Susi Cahn, who is from the family that founded Coach Farm goat cheese — and, not to mention, owned the Coach handbag brand for half a century.)

Batali was an unusually impassioned salesman, acting as if Falstaffian uncouthness were simply a function of his grand appetites. On television and in interviews, he came across as a gregarious polymath able to hold forth “on anything from regional Italian cooking to papal history to sports to politics — speaking in full paragraphs and without notes,” says another food editor. Critics adored Babbo for such lavish paeans to umami as Batali’s beef-cheek ravioli and lamb’s tongue with black-truffle vinaigrette. The Times awarded the place three stars in 1998 and again in 2004. In the latter review, Frank Bruni explained that what prevented it from becoming the only Italian restaurant in the city to merit four stars was, simply put, the “jarring” Led Zeppelin music blasting into the dining rooms.

“It was really a thing to play loud rock and roll at all times, and the first move Mario made when he came in at night was to put it on or turn it up,” says Adam Reiner, who runs the website Restaurant Manifesto and was a server at Babbo. Batali insisted that entire sides of albums (or, in the case of Beggars Banquet, both sides) be played from his iPod. If guests asked if it could be turned down, the answer was a polite but firm no. “We wrote the rules, because we felt we knew better,” says Reiner. “Now it feels like a pretty tight encapsulation of his whole arc — the air of invincibility, the satisfaction Mario got from saying, ‘Let’s just try this and see what happens.’ ”

Batali was intoxicated by “the excitement he created when he entered a room,” according to one friend. “He saw himself as untouchable, and it brought out the worst in him around women,” Elisa Sarno, a former chef at Babbo, says. “I once told him it would be nice just to have 10 percent of his ego. He was so full of himself — but encouraging, charming, all that crap. Maybe his fame made him think he could do whatever he wanted.” Sarno once complained to him about one chef’s habit of referring to broccoli di rape — Italian for broccoli rabe — as “rape” (the Italian pronunciation is RAH-pay). Batali’s response was “This is New York. Get over it.”

Another woman who worked at Babbo says, “Everything was sex with him — he was constantly lewd and ogling women, thinking he was just being funny, and people laughed it off. He grabbed my ass when I was about one month into the job. I went and found him on the phone a few minutes later and told him never to do that again. He was surprised, but I wouldn’t exactly say he was scared. To his credit, he never did it again. But I saw his behavior get looser and looser, and I tried to give him the benefit of the doubt. He really thought it was something he could do — grabbing women by the crotch, kissing them at the bar. If you worked for him, you were afraid of saying something and getting blackballed.”

And it wasn’t just the people who worked for him. The Washington Post reported that at a Vanity Fair event featuring him as the celebrity attraction, he sized up an employee charged with introducing him to guests and told her, “I want to see you naked in my hot tub back in the hotel.” In a video one woman shared with Eater, Batali tried to French kiss her when she asked him for a selfie.

Lori Lucena, a former service director at Otto and, later, general manager of a group of B&B restaurants in Las Vegas, devised a method for trying to keep Batali happy but still at some distance from his worst impulses. “I had to make sure that if Mario and Joe or whatever VIP friends they sent were coming in that night, I would put my less attractive women or a male server on the last shift — to kind of ward off any debauchery,” she says. “That was my way of protecting my staff, but when you think about your guilt, you wonder, What did we do to enable the problem? Like, why couldn’t we have just said this is not okay?”

Even several former colleagues who spoke at Batali’s request express remorse for having tolerated his creepy jokes, his hitting on everyone, and, as one puts it, “all the groping and all the hooking up in the bathroom with women who weren’t his wife.” “Mario’s a pig, and a lot of us ignored it because at his best he’s delightful company,” one friend of his says.

Spotted Pig owner Ken Friedman — who also faces a number of sexual-misconduct allegations — has told associates that, about five or six years ago, he had gotten so many complaints from his staff that they refused to work late nights in the upstairs room if Batali was coming in. He said when he told Batali he was unwelcome there, Batali responded, “Fuck you,” but mostly refrained from showing up. That was when Batali began using the apartment upstairs from Babbo, where the 2004 assault is alleged to have occurred. (In a brief interview, Friedman would not discuss Batali but denied that the third floor of the Spotted Pig was ever called the “rape room.” “I have never heard the third floor referred to as that, not once, nor has anyone I have ever worked with or associated with,” he said.)

Julie Panebianco, a friend of Batali’s who puts on charitable productions for the music and restaurant industries and was involved in introducing Batali to many of the rock figures he befriended, says that, around this time, she grew concerned for him after a series of “drunk and obnoxious” episodes. She confronted him “and he froze me out.” He avoided her socially and stopped hiring her to plan events for his foundation. “He told several artists and celebrities we were no longer friends because I’d insulted his wife.”

It’s mainly the people still involved in the B&B empire who profess not to have been troubled by his treatment of women all along and claim they never saw anything untoward. The chef Nancy Silverton, who founded four Mozza restaurants in California with Batali’s imprimatur and was promoted to a leadership role in the restaurant group, said by telephone from Umbria that “he was an important part of what I did in L.A., but in terms of hours spent in the same room, we didn’t really work that closely together.”

Silverton called him a friend and spoke admiringly of his influence as a chef. Just before she hung up, she said she hadn’t talked to Batali since she learned of the allegations against him: “I’m still in mourning.” A few minutes later, she emailed because she was concerned that the sentiment could be misinterpreted. “I don’t want to diminish the pain Mario’s inappropriate behavior has caused his victims. That is very important to me,” she wrote. “I want to emphasize my empathy with the victims, and, because of that, Joe’s and my path to separate was immediate.”

Batali’s origins include a self-described “stoner” childhood outside Seattle and stints at Le Cordon Bleu and the kitchens of Stuff Yer Face (a pizzeria in New Brunswick, New Jersey) and a London pub, where he apprenticed to future legend Marco Pierre White. Along the way, he spent time in the undergraduate theater department at Rutgers — the actor James Gandolfini was a roommate — and he brought that dramatic pedigree to bear on his culinary career. He went on to host a cooking show with Gwyneth Paltrow, voice a character in Wes Anderson’s animated movie Fantastic Mr. Fox (Rabbit, a chef), and make cameos as himself on Saturday Night Live and The Simpsons. According to From Scratch, a history of the Food Network by Allen Salkin, executives were at first troubled that Batali appealed more to men than to women, the target audience for their advertisers. “But Batali was an inspiration to new arrivals for his ability to cook and tell stories at the same time — the high art of cooking shows and the rarest skill,” Salkin says. Chefs who came in for auditions were shown footage of Batali and instructed to mimic his cadences.

Batali’s emergence in the 1990s marked “a tectonic shift in how great chefs were viewed socially in America,” says Mark Ladner, a protégé who helped start Lupa and Del Posto. “He was the Sammy Hagar of food, a rock star.” With his own line of Crocs (these were more like chef’s clogs, though the company also designed a special model with golf spikes for him), it wouldn’t be a great stretch to consider him the Michael Jordan of the culinary industry.

Pó, Batali’s first, tiny restaurant on Cornelia Street, had been highly regarded, and he had his own popular cooking show, Molto Mario, on the nascent Food Network when he joined forces with Bastianich to open Babbo in 1998. The 90-seat, split-level dining room changed how New Yorkers ate, elevating Italian cooking to a status enjoyed by only a handful of French chefs and energizing a tired downtown landscape. Babbo’s chic menu made generous and innovative use of nose-to-tail parts and organ meats, and Babbo was where the back of the house (the kitchen) became known somehow as having supplanted the front-of-the-house staff as the theatrical heart of the dining experience. For those who worked there, its sink-or-swim culture felt like a philosophical hybrid of the Marines and backstage at Max’s Kansas City.

“It was epic in its time. Mario’s kitchen was intense,” says Andy Nusser, Babbo’s opening executive chef, who tells the story of having met Batali in Santa Barbara when they were in their 20s: “Someone had brought foie gras, and Mario looked in the kitchen and made a reduction sauce for it out of orange soda and Starbursts.” Batali told his chefs that he saw his restaurants as inhabitants “of the corner of art and commerce,” and he had a fanciful way with words as well as offal. In Heat, Buford recounts how Batali brought a giant slab of home-cured lardo — the entire fatty back of a pig — to a dinner party, insisting on placing pieces on everyone’s tongue and explaining that, in the final months of its life, the animal from which it had come subsisted on a diet of apples, walnuts, and cream, which he described as “the best song sung in the key of pig.”

Meanwhile, the B&B group expanded its portfolio: Lupa (Roman trattoria), Otto (pizzeria and wine bar), Bar Jamón (tapas), Esca (fish), and Del Posto (which did finally earn that four-star Times review). Batali published a raft of best-selling cookbooks and later starred on ABC’s The Chew. (His television contract was canceled in the wake of the allegations.)

In his memoir, Restaurant Man, Bastianich lauds his partner’s skill at the art of compiling a seductive bill of fare: “When it comes to writing menus, Mario is like Kurt Vonnegut meets Einstein — he knows how to create the document that does it all … There hadn’t been a menu quite like Babbo’s before — it is very creative but also very easy to understand, and it opens the doors to infinite possibilities of putting together a three-course meal.” He also describes one of the duo’s rare failures, a short-lived retail wine venture — after three years, they sold it at a loss in 2008 — whose demise both men blamed on a third partner from Naples, whom Bastianich’s mother, the restaurateur Lidia Bastianich, had apparently tried to warn them away from.

“When we took a $2 million haircut on this,” Bastianich writes, Batali told him, “You should have listened to your mother, you douchebag. Don’t get into fucking business with a sawed-off Neapolitan fuck. Anyone with a small penis is no one you want to have business with. Only guys with big swinging dicks.”

Bastianich adds that Batali “meant that existentially, of course.”

While Batali agreed in May to let Bastianich and various other partners buy him out of his ownership stake in their restaurants, negotiations have missed several deadlines (they had initially been set to close by July 1) and have continued, more than five months later, to drag on without resolution. Lawyers involved acknowledge there’s difficulty in getting Batali to yes. On the one hand, the properties would never have existed without him and were built in his own image. On the other, how much is that image worth now?

“Mario isn’t about to let himself get taken advantage of by Joe because of the situation,” Ladner says. “They have a tumultuous relationship, and they’re both very serious businessmen and entrepreneurs. Someone’s got to win, and someone’s got to lose.” Some partners speculate that Batali’s share might have been worth $100 million at its peak and certainly remains in the tens of millions. It’s also unclear what will happen with Eataly America, in which both Bastianich and Batali are investors (some of Batali’s friends say he hopes to retain his equity). According to someone involved in the negotiations, the two men considered trying to offload large quantities of valuable wine to finance Batali’s buyout.

How capable is Bastianich of propping up the business without Batali? Even during boom times, Bastianich was possessed of a world-weary cynicism. As a fixture of such TV reality shows as the American and Italian versions of MasterChef and CNBC’s Restaurant Startup, he is a reluctant and cranky judge. An internet-message-board commenter once described him as “antisocial and loathsome,” and Eater made note of his “vitriolic critiques.” His parents, Felice and Lidia, emigrated from Istria — a peninsula within the former Yugoslavia, just across the Adriatic from Venice — to Queens, where they ran a popular red-sauce joint. Eventually, they opened Felidia, a trailblazing restaurant on Manhattan’s East Side. In Restaurant Man, he writes of his calling, “It comes down to a very simple concept … We buy things, we fix them up, and we sell them for a profit.” Bastianich and Batali were a successful front- and back-of-the-house team with an uncommon division of labor. While Batali’s dual genius as chef and public face rendered him, in a sense, both Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside, Bastianich was left to function not so much as a complement to his partner as a strategic consultant.

When people talk about Bastianich’s particular skill set, they mention his facility with real-estate deals and small, stylistic flourishes: bringing French-style service to Italian restaurants, crumbing tablecloths with a spoon, establishing the legitimacy of eating at the bar in a fine-dining restaurant, offering wine in quartinos — “the pomp and circumstance of wine-by-the-bottle service in wine-by-the-glass consumption,” as Bastianich writes. Most everything has to do with the hybridizing of high and low and subtly turning it into part of a brand that might be classified as “exalted-taste renegade.” The question now is whether that food philosophy can exist as a brand without Batali — and whether diners want it to.

The two partners had drifted apart over the years, though Bastianich has always been vague about why. “We were friends until we weren’t friends” is how he tends to put it. Many people say Bastianich resented Batali’s star power and glamorous friends. Over a decade ago, Bastianich, who had struggled with his weight, lost more than 60 pounds by drinking less and running marathons, and he found the personal transformation heady. He began appearing on TV, spending months at a time in Los Angeles and then Milan to star in several food-related shows. He came to see himself as a celebrity in his own right. But the TV persona Bastianich developed as a reality-show judge — grumpy, dyspeptic, mean — is not the stuff of which restaurant empires, no matter how distressed, are remade. “It wouldn’t hurt if Joe started smiling a bit now, maybe put some Vaseline on his teeth,” concedes Nusser, who remains a partner in four Bastianich restaurants. “This is the hospitality industry.”

The restaurateur Drew Nieporent, who founded Bâtard, Tribeca Grill, and Nobu and has been Bastianich’s friend and mentor since before Babbo opened, says, “Joe didn’t make friends — that was Mario’s job. Now it’s up to him to be that guy. For him, it’s a lonely place. I have no idea who goes to Babbo now, but it’s still in business nearly a year after Mario left, so that means something.”

One Babbo regular — a friend of both Batali and Bastianich for decades — ate there recently and still found the food “terrific,” he says. “But the loss of charisma to the place was palpable. Joe was looking after the room, but without Mario there was definitely the feeling of an absence. The prices are the same, but it felt expensive in a way that it never had.”

When these critiques were presented to Bastianich over lunch at Babbo, he said, “Welcome to my world.” He also took issue with someone calling Babbo expensive. “It’s a real value, especially the pasta tasting menu,” he said, calling out to a waiter to ask what the restaurant charges for it.

“A hundred and five dollars,” came the reply.

“No, not the regular tasting menu, the pasta tasting menu,” Bastianich said. But that was the price for the pasta tasting menu. “That’s expensive,” Bastianich said, reconsidering.

A bit later, he added, “I’m still not the showman, the charmer. I have no intention of becoming the public face of the restaurants.” Some of that responsibility, he said, would fall to his mother and Nancy Silverton, though they were all moving away from the risky business of building a corporate identity centered on a celebrity chef in the first place. “It’s really about eliminating the grand wizard and elevating all the other people, harvesting all that talent. That’s what I have. Those are my resources.”

Executives of the company say the least-affected B&B restaurants are the outposts in California, Westchester, and New Haven. Still, with Batali’s disgrace, the numbers are down at all of them, Bastianich said, particularly at Babbo, Lupa, and Otto, “the most Mario-centric places.” La Sirena, which opened in Chelsea in 2016, will close at the end of the year. There has been talk of bringing in Silverton or Lidia Bastianich to run Otto, which has also been hard hit. That was where you used to find Batali most frequently, situated as it was on the same block as his apartment and “the most neighborhood based” of the lot. “The cult of personality was big there,” Bastianich said.

Meanwhile, Batali’s victims continue to demand justice. The woman who claimed he’d kissed her when she requested a picture with him filed a sexual-assault lawsuit in Massachusetts in August. According to the complaint, he also “rubbed her breasts, grabbed her buttocks, put his hands between her legs and groped her groin area, and kept forcefully squeezing her face into his as he kissed her repeatedly.” The Boston police have referred the case to the Suffolk County district attorney’s office, according to her lawyer.

For several months after his ouster, Batali was far from invisible. People saw him every morning on his laptop in the lobby of the Marlton Hotel or riding his Vespa around town with an orange messenger bag slung across his shoulder (orange Crocs, orange beard, orange cargo shorts: His brand was a warning signal disguised as buffoonery). Telling friends he was contrite but upbeat, Batali seemed to have embarked on a rather public journey of self-repair. He sent updates from abroad as he volunteered on a series of humanitarian projects, teaching courses in commercial cooking and restaurant operations to groups of migrants and refugees in Rwanda, Greece, and Iraq.

“He texted me a picture from Mosul,” said Nusser. “He’d lost a lot of weight. He said it’s because he quit drinking.”

By the summer, after the 60 Minutes story aired, Batali was no longer being spotted in the city. His lawyer, Cathy Frankel, and his PR representative, Risa Heller, would not discuss his whereabouts, and others who keep in touch with him were evasive. “He’s working on himself,” said a former colleague. “I can’t say more.” A friend said, “He’s reevaluating his life. He’s someplace quiet.” Another friend said, “He’s not even thinking about the future — right now he can barely think about the present — so give him space.” A booker for one of the morning TV shows who had been trying to land an interview with Batali said she was pretty sure he was working on a farm “somewhere in Italy.” “He’s not in Italy,” yet another friend said.

Since 2003, Batali and his family have had a summer house in Northport, Michigan, at a former trout-fishing camp where he installed an outdoor pizza oven shipped from Italy. He likes to golf two or three times a week when he’s there; last year, he told Bloomberg News he brought down his handicap from 17 to 10 by changing his stance and follow-through.

Batali fell in love with the Leelanau Peninsula — the tip of the pinkie side of Michigan’s mitten-shaped landmass, where Northport is located — more than 20 years ago while visiting friends of his wife. It was once a Gold Coast for Detroit’s manufacturing dynasties; the founders of Dow Chemical and the Ball jar company have called the area home. And Michigan celebrities spend time there: Tim Allen, Kid Rock, the Ciccone family (Madonna’s father owns a winery). The Edge from U2 once visited Batali’s house before the band played a concert in Chicago.

As it happened, it took me only about six hours to find Batali in Northport. After a search of the weekly farmers’ market, Dog Ears Books on South Waukazoo Street — where one resident warned that Batali comes to Michigan to be left alone (“Although he drives a bright orange Dodge Power Wagon that everyone knows. You could cross the Klondike in that thing”) — one restaurant, and two happy hours, I found him on the Northport green, where several hundred people had gathered in front of a bandshell, drinking white wine and sitting in folding chairs. A two-man electric-folk combo, Mulebone, played covers while children and elderly people danced in a few small clusters. A breeze blew in from Lake Michigan.

Midway through my first loop around the crowd, Batali came into view: on a canvas chair in a fleece vest, a baseball cap, and those Crocs. He sat with a group of other middle-aged couples, a picnic blanket before them and a table laid out with cardboard platters of food. Occasionally, someone approached Batali to say hello, but for the most part he was undisturbed and nodded along to the band. The cover of “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” featured an extended free-form flute solo. Batali raised both fists.

A break came in the music, so I began walking over to him. “I know who you are,” he said when I introduced myself. “It’s nice to meet you.” Batali declined to be interviewed. “And the reason is, I’m not going to live my life in public anymore,” he said.

How long would he stay in Northport? “At least until the end of the year,” he said. (In November, he was spotted in New York, but friends say he has no plans to return to the city permanently.) Anyone could see, I said, why he likes it so much there. “I’m a lucky man,” Batali said, then seemed to register how this must have sounded. “Well, it’s been a bad year,” he said, “a bad year.”

When I turned to leave, Batali couldn’t help but revert to instinct. “Here, let me at least make you a plate of food,” he said. He leaped from his seat and did just that — barbecued chicken legs, Asian slaw, roasted vegetables, guanciale, and “the best tomatoes you’ve ever had” — with a pale-yellow sauce that came from a jelly jar. All of it was terrific, but that was never the question.

*This article appears in the December 10, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

*This article has been updated.