When Manal Kahi and her brother Wissam founded their catering company Eat Offbeat in 2015, they didn’t just want to feed New Yorkers. They wanted to change the story around refugees in America. The Kahis are originally from Lebanon, and their grandmother hails from Aleppo. It was the ongoing humanitarian crisis there that gave them an idea: a food business that exclusively employs refugees.

To find employees, the Kahis collaborated with the International Rescue Committee, a nonprofit that helps refugees resettle and find jobs. The only condition was that they needed to have sharp culinary skills. That’s because Eat Offbeat’s employees, who all happen to be women, aren’t making chicken club sandwiches and other typical catering cuisine. They set the menu themselves, with their own marquee dishes, like Nepali momos and Iraqi biryani.

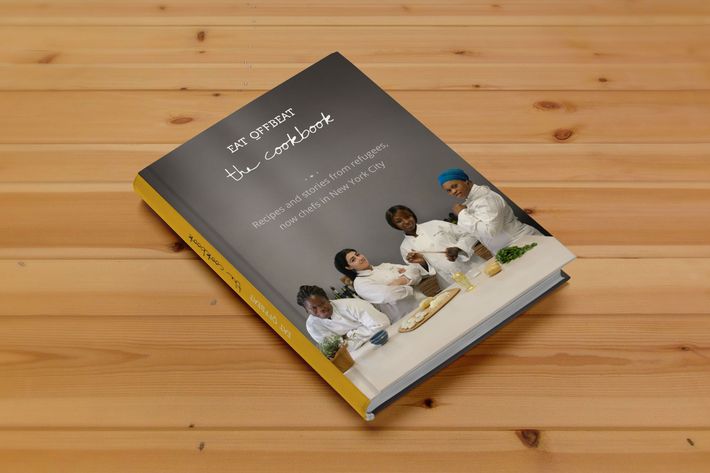

With this mission, Eat Offbeat stands alongside League of Kitchens, the recreational cooking school that empowers immigrant women, and Hot Bread Kitchen, the Harlem bakery-slash-social enterprise that teaches immigrant women how to bake and sells breads inspired by their ancestry. And now, Eat Offbeat will bring these dishes and stories to an even wider audience with the first cookbook, Eat Offbeat: The Cookbook, written by refugees — though Manal is quick to emphasize that they strive to present a more complete picture of the women.

“The whole time in making the cookbook and just in general, we’re asking, ‘how do we still describe what we’re doing without reducing our chefs to their status?’” Manal says. “It’s not about helping the chefs — they don’t need help. We want to show them that they are the ones helping us. We want them to be proud of being featured there.”

Last week, the company surpassed its Kickstarter campaign’s $50,000 fundraising goal. It just took ten days to achieve that, with people from 32 countries contributing to the campaign. (That money will also be used for the book, and to hire new cooks. Ten percent will go to the IRC.) Encouraged by the response, Eat Offbeat is now announcing a stretch goal of $100,000, which — if met — will be used to hire yet more cooks and, excitingly, launch a cooking-channel companion on either YouTube or Vimeo. (Backers will receive free access, while others will pay, and it will be continuously updated.)

Right now, the plan for the book calls for 80 distinct recipes from 20 different cooks. All of the recipes will be tested, in order to ensure that they’re accurate and can work for other cooks, by Eat Offbeat culinary officer Juan Suarez de Lezo, who worked in the kitchens of such well-regarded restaurants as Eleven Madison Park and Per Se. Currently, 17 cooks have committed themselves to the project, and Manal hopes to represent 15 different countries. What she wants is to give the cooks an opportunity to share a dish they excel at and they love. So Bahia, originally from Algeria, will contribute “an incredible couscous”; while Mitslal, who hails from Eritrea, will bring her version of the lentil dish adas to the table. Meanwhile, Minata, who was born in Guinea, will contribute the West African staple of peanut sauce with rice.

“Everyone has at least one dish they’re really good at or know really well,” she says. “We want that one dish. But some people have five or six!”

Manal adds that these are dishes from home cooks, and the degree of difficulty will reflect that. What they want is to create a reliable, well-crafted, and professional resource for home cooks — one that just happens to be a collection of recipes by a cadre of skilled cooks who came to this country as refugees. To that end, they’ve hired the Dutch food photographer Signe Birck — who worked on projects from acclaimed chefs including Ronny Emborg and Daniel Burns — and are currently in negotiations with a writer. Since the campaign was launched, publishers have approached the company, but Manal says their priority is to do whatever will help them create a “top-notch book worthy of our chefs.”

The purpose of the project, however, extends far beyond giving readers a glimpse into different cuisines as they exist today or, say, how to properly cook lentils the Eritrean way. It will share the stories of the chefs themselves, explaining why they’ve chosen particular recipes, and what the dish means to them. It will go into the personal tweaks they’ve made along the way, whether because of an allergy or in favor of a particular ingredient. More importantly, it’s about giving a voice to these often-voiceless people. Ones whose own stories they often have little control over, and who are almost always whittled down to simply being victims.

“We want to tell the success stories of these chefs, who are now being featured in — we want people to see them for the chefs they have become, and the heroes that they are. We want people to see way beyond their status as refugees,” Manal says. “Since we started, part of our mission has been to change the narrative around refugees. What better way to change the narrative than to write a new one?”