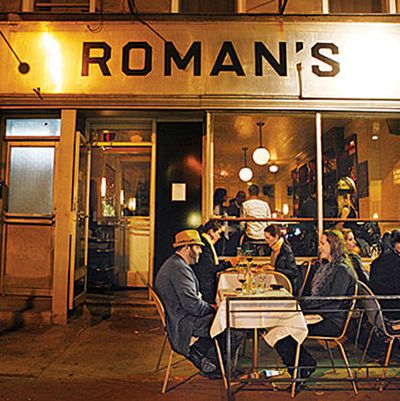

The tipping debate is easily the most-talked-about issue in New York’s food world, spurred on by Danny Meyer’s announcement that he would convert all of his Union Square Hospitality Group restaurants to a service-included model. Other pioneering owners followed suit, including Andrew Tarlow, arguably Brooklyn’s most influential restaurateur. He revealed in December that he too would go gratuity-free at his family of popular restaurants, starting with Roman’s, the bustling Italian spot in Fort Greene. At the time, another big-name convert was something of a coup for no-tipping advocates, but in the ensuing months, the transition, it seems, has not been without problems of its own.

“Part of what made the change so difficult is just actually undoing the way we’ve been programmed,” says an employee of Roman’s who asked to remain anonymous. “Of course, it’s been weirdly emotional and frustrating and anxiety-causing.”

Management is sympathetic to those feelings: “It has been, I think, challenging for the front of house to change the way we do things and the way in which they are compensated,” human-resources and company rep Leah Campbell tells Grub. She said that it was more than a simple change, and likened the move to “rebuilding the foundation” of the restaurant group.

Roman’s moved to a gratuity-free model on January 18. The plan is that, over the next few years, the restaurant’s kitchen workers will see their starting wage rise to $15 an hour. Servers, meanwhile, now receive a wage of $15 to $17 an hour in addition to earnings from a revenue-share program, a kind of tipping substitute that buoys their wages after the loss of tipping. It’s a similar system to the one Meyer uses at his tip-free restaurants, as well as gratuity-included spots like Fedora, or Huertas in the East Village, which is notable for including both front-of-house employees and line cooks in its revenue share.

While servers who have seen their pay go down as a result of the changes, as well as those who fear the change, grumble about the transition, they’ll admit that the previous system of tips — basically just semi-arbitrary amounts of money from the public — is antiquated. “What other kind of industry is there where you can own a business and not have to pay anyone because you’re relying on the clientele to pay for your staff?” asks the Roman’s employee. “I just think it’s really a broken system.”

Even still, New York is an expensive place to live, and it’s understandable that workers would feel uneasy about any destabilization of their income — even if they know their co-workers aren’t paid fairly. The management at Roman’s didn’t do itself any favors with the timing of their announcement: The restaurant’s staff was notified of the switch on December 15, the same day the public was told.

After the change was instituted on January 18, servers took a pay cut from what was, Grub was told by employees and former employees of Roman’s, an income well above average for the industry — something like 15 to 20 percent so far. Not everyone was onboard with such a dramatic drop. One veteran server promptly quit. She had been at Roman’s since 2011 and with Tarlow’s restaurants for several years before that.* Another server followed suit, but everyone else stayed, and Campbell says the turnover rate is the same as in previous years. (Roman’s typically employs seven servers at any one time.)

“It’s virtually impossible to go along [with making] less money in NYC,” says Roman’s bartender Anna Dunn, who has worked for Tarlow’s company for a decade and is now the editor-in-chief of the restaurant group’s Diner Journal. “I want to support people in the back of the house. It takes time to recognize that it’s not a personal thing but something that will benefit everyone.”

The current restaurant employee points out that a pay cut like this — probably necessary but no less frustrating as a result — inspires feelings that you might call mixed at best. “If they’re going to present it to us, or to anyone, as about evening the wage gap between the back and front — which it isn’t actually doing now — the back of house is still getting paid very little and a lot less than the waiters,” the source says. “But if you’re going to make it about that, why weren’t you just paying the people cooking the food fairly, you know, ten years ago?”

“The servers are being asked to sacrifice. We did it in the slowest possible time of year, are raising prices 20 percent, and are seeing regular business. It’s hard to justify giving servers anything more,” says Roman’s sous-chef Frank Reed. “I believe it was a change that was inevitable and coming. Disparities between back and front of house were never going to get fixed.“

Those who have stayed at the restaurant are supportive of the change. Dunn says the mood is far less contentious than it was when the change first took effect. Conversations between the waitstaff and management have increased, too, she says, but it’s also clear that ending tipping could change the dynamic of serving and who can make it work.

“Some people want to pursue their art for 40 hours a week and then work 28 hours a week in a restaurant to pay the bills,” Dunn says. “Those people are really vital to a room. What are they going to do to make the most amount of money in the least amount of hours?” She says that, before, some workers could count on big paydays on busy nights and focus only on working those times. The move to the no-tipping system means it doesn’t matter in the same way how busy the dining room is. “I think about how people can’t pick up a Friday shift and earn a ton of money to make up for having to take a week off to write.”

*This post has been edited. It originally stated that the server in question had worked at Roman’s since it opened, but a rep for the restaurant says the person started in 2011.