The concept of paying for a table at a restaurant is hardly new. For as long as there have been hosts and maîtres d’, there have been customers willing to slip them a $20 for entrance into a packed dining room. Tactful, elegant, and, if done correctly, immensely satisfying. Alas, it seems like a dying art form, and now, even the simple act of greasing somebody’s palm is entering the digital realm — not everyone is sold on the idea.

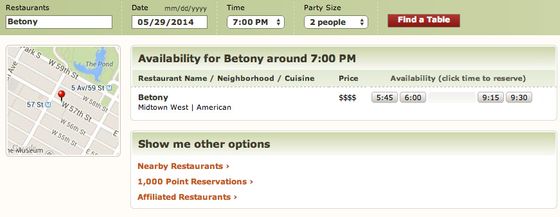

The pay-for-reservations industry is young, but it’s nevertheless competitive, mostly owing to scaling operations like Killer Rezzy, which snap up restaurant reservations and charge people to use them. This is, of course, a truly loathsome service, but at least we can comfort ourselves knowing that people who rely on it are idiots: This morning, the Killer Rezzy homepage advertised a 9:30 p.m. two-top at Betony tonight for $25. Meanwhile, OpenTable listed a 9:15 p.m. reservation for two that could be had for free. These two screenshots were taken about one minute apart:

Even when customers use reservation scalpers, restaurants don’t see any of the action. That’s where an app like Resy comes in. It serves as a middleman, but it also partners with restaurants, so they get a cut when a customer ponies up for a last-minute table. Here’s how Resy’s co-founder Ben Leventhal explained it to Eater yesterday:

…[E]ach of the restaurants on Resy are turning over some of their reservations to us so we can offer them to customers, to our customers. Those tables will vary in price, two bar seats on a Tuesday night at Charlie Bird might be ten bucks a piece and Saturday night at Minetta Tavern might be closer to fifty.

Fom a diner’s standpoint, it’s tough to see any difference between Resy’s model and paying someone off at the host stand: slip the restaurant some (digital) cash and you’re in. The beauty of the analog deal-sweetener is that it happens when nobody’s looking. It requires real talent and skill to execute properly. Open this idea up to anybody with an iPhone and suddenly people see it as a simple surcharge.

If restos levied a direct surcharge on 8pm tables, the ill will would be huge, I’ll bet. So an app, like tickets, may shield them. Maybe.— Pete Wells (@pete_wells) May 28, 2014

Yet the problems that an app like Resy addresses are real: It’s a pain in the ass to get into hot restaurants at prime times, and owners don’t do enough to profit off of increased demand. Here’s where the pay-for-reservations approach feels skewed, though: Diners still see the cost of eating out as money that pays for a meal, not a table. In other words, restaurant customers will pay for an experience, but they tend to balk when they’re asked to also pay for access to that experience.

So, what can an owner do that won’t immediately alienate customers? Adjust the price of the experience itself. It’s an idea that’s gaining traction. Look at the ticketing system that Grant Achatz and Nick Kokonas use at their Chicago restaurants. It’s simple: Go online to book a table and pay the entire cost of the meal up front; the site explains that the price of the meal fluctuates, slightly, based on demand. The system has been such a success that Achatz and Kokonas will soon offer the service to even more restaurateurs.

Even Chez Panisse, America’s ultimate analog restaurant, understands this very straightforward principle. The restaurant’s prix fixe menu costs $65 on Monday, $85 on Thursday, and $100 on Fridays and Saturdays. The menu changes nightly, which can signal to diners that the different costs are owed to the different ingredients, but it’s obviously no coincidence that the most expensive nights are also the busiest. (Restaurants that don’t offer set menus can adapt by adjusting the prices of their à la carte items accordingly. In an era when nearly every hot restaurant tweaks its menu daily, anyway, it isn’t difficult to adapt Chez Panisse’s adjustable pricing to individual dishes.)

Restaurants do need to rethink the way they charge customers, and diners have proven they aren’t entirely resistant to the idea that dinner can cost more when demand is higher. But restaurants are in the hospitality business, and few things feel less hospitable than explicitly charging extra for something that used to be free — which is why adding that extra cost into the overall price might be the system that proves most successful.