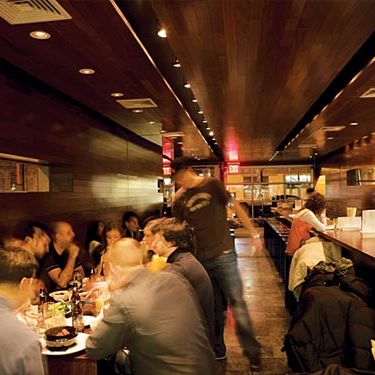

Even as recently as six or seven years ago, restaurants were still places where you made a reservation, sat down, ate an appetizer and then an entrée, had coffee with your dessert, and left. But now we’re dining in a new era of restaurant. You know the kinds of places I’m talking about: No sign out front; the bartender maybe has a carnation in his lapel; food is served on carving boards and granite slates; something vintage in the decor (taxidermy, rotary phone, estate sale cutlery); definitely no tablecloth in sight. Most of us have happily dispensed with the blazers and sauce spoons of the fine-dining era and are relieved to do away with archaic formalities like standing when a lady leaves the table. But are there new Ms. Manners–style rules by which we must abide? Well, not exactly rules, but there are some things to keep in mind.

Bars are for diners, not just drinkers.

In some smaller restaurants, people eating (and thus spending more money) will be given preference at a crowded bar. This can obviously be annoying for someone just hoping to grab a cocktail, but you can use it to your advantage: Restaurants rarely take reservations for bar seats, and they’re often first-come, first-serve. If you let the host or bartender know that you’re planning to eat at the bar, they’ll often (graciously) shoo other people away from any available stools.

You can wait for a table wherever you want — including the bar next door.

Let’s discuss navigating the controlled chaos of “no reservations” establishments. When possible, give your cell-phone number to the host and head to the closest bar. If it is freezing or pouring or the wait promises to be short, just order a drink and do your best not to trip anyone carrying soup. At Joseph Leonard, where diners have taken to resting drinks on a stack of vintage suitcases while they wait, Gabriel Stulman says that “bumping into people is part of the charm.” There is a certain style to this, for sure; whether it is yours is a matter of taste and circumstance.

If a server or bartender does ask you to move, you should do so. The restaurant isn’t trying to make you uncomfortable or disrespect your space (they want you to stay, after all) — you probably really are just in the way.

As for those moments when your wait for a table seems to drag on, whoever is working the door should give you a time frame when putting your name on the list. Add at least five minutes to that time before you check in — and remember that hounding them is only going to irritate them, not get you a table any sooner.

Be flexible about where you are seated.

We all know that restaurants have good and bad tables, but for your own sanity let go of the antiquated suspicion that you are being judged by where you are seated. God bless the host faced night after night with entitlement and indecision, especially now that there are so many nontraditional options: the bar, the chef’s table, and the communal table, to name a few.

If you are looking to get seated at a specific table because you’re planning to propose or something, call the restaurant ahead of time and give them a heads-up. Unless you’re an investor or movie star, your dream of strolling into Minetta Tavern unannounced and getting a corner booth using nothing more than your charm and a palmed $20 is going to have to go unrealized.

You don’t have to talk to strangers at communal tables.

Ah, communal tables. They inspire much eye rolling. But restaurants like them because they provide a grand table for larger parties without the cost of a private room or having to sacrifice smaller tables. Diners are less enthusiastic. A friend recently hypothesized that people in San Francisco embrace the communal table in a way that we cynical, standoffish New Yorkers do not. I called Alex Fox, GM of Bar Tartine in San Francisco, to see if this was true. Nope, same stigma. “You know where people really like communal tables?” he said. “Chicago.” But I suspect that we would find the same answer in Chicago. It’s human nature; we don’t like eating in front of strangers, we like the intimacy of breaking bread with those close to us.

The best bet when seated at a communal table is to smile, nod, or utter a greeting, and then proceed cautiously with any further communication. You might end up making friends and sharing a bottle of wine, but nobody will think less of you if you don’t.

And a note on using bags as a means of claiming extra space or seats in communal situations: don’t.

Treat your server as a resource, not as a servant.

Do not be fooled by the tats and nose rings; servers in many newer restaurants know from whence the restaurant’s mache came and the name of that edible flower that’s been carefully tweezered atop your plate. Ask questions — and not just their favorite item on the menu. But be careful: You don’t want to turn dinner into a quiz about a dish’s provenance. And if the server is unsure, just ask them to check with the kitchen.

Good restaurants will make a point to let their servers know that they’re the bridge between kitchen and dining room.

Order whatever you want, whenever you want it.

You are hereby released from any obligation to order one appetizer, a main course, and a dessert. The benefit of the small plates that are running rampant on menus now is that they allow you to construct your meal however you wish.

John Adler, one of the chefs at Franny’s, encourages people to ask questions, look around and see what other diners are eating — and, most important, to get excited. A good kitchen and service staff will be able to pace your meal and suggest an ideal order.

Be ready to share your food.

Embrace what Marcia Gagliardi, of Tablehopper in San Francisco, calls “flavor tourism” and share a bunch of dishes. This might mean ignoring Emily Post and reaching across a table or shuffling plates around — double dipping be damned.

If you are dining with someone you know less intimately or with someone whose pace of eating differs greatly from yours, you can ask the kitchen to split the dish (keeping in mind that this is not always possible). The best move is to just let your server know when you order that you’ll be sharing everything. They should be ready to accommodate accordingly.

Don’t linger when you’re done.

Do not be fooled by any tattered hardcovers beckoning from a shelf nearby. You are not to read these. Gone are the days of cocktails before opening a menu. During prime dining hours when there’s obviously a wait for tables, enjoy yourself and move on.

If you want to linger, plan to dine early or late and speak honestly with your server or host. Ask if they need the table back right away. If they do, they will most likely make you comfortable at the bar. If they don’t, they’ll be grateful that you asked and you’ll savor your dessert in leisure.

As much as we might want our table for the evening, as Gagliardi puts it, “There is a contract between diners and restaurants. You want them to stay in business and they want you to come back.”

And yet, the most important thing to remember is that this is just dinner we’re talking about, and you’re going to a restaurant to have a good time. The staff is there to facilitate that good time — so be accommodating and respectful, and a restaurant will go out of its way to do the same for you.

Phoebe Damrosch is the author of Service Included: Four-Star Secrets of an Eavesdropping Waiter.

Related: The Crowded Restaurant Conundrum: Why We’re All Gluttons for Punishment